Interim Report: Blue-Ribbon Panel on the Prevention of Foodborne Cyclospora Outbreaks

The 1996 cyclosporiasis outbreak in the United States and Canada associated with the late spring harvest of imported Guatemalan-produced raspberries was an early warning to public health officials and the produce industry that the international sourcing of produce means that infectious agents once thought of as only causing traveler’s diarrhea could now infect at home. The public health investigation of the 1996 outbreak couldn’t identify how, when, where, or why the berries became contaminated with Cyclospora cayetanensis. The investigation results were published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1997.1 I was asked to write an editorial to accompany the investigation report.2 In my editorial, I noted the unknowns surrounding the C. cayetanensis contamination. The 1997 spring harvest of Guatemalan raspberries was allowed to be imported into both the United States and Canada—and again, a large outbreak of cyclosporiasis occurred. As in the 1996 outbreak, no source for the contamination of berries was found. Later in 1997, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) prohibited the importation of future spring harvests of Guatemalan raspberries until a cause for the contamination could be demonstrated and corrective actions taken. While the FDA did not permit the 1998 importation of the raspberries into the United States, the berries continued to be available in Canada. Outbreaks linked to raspberries occurred in Ontario in May 1998.

The 1996 cyclosporiasis outbreak in the United States and Canada associated with the late spring harvest of imported Guatemalan-produced raspberries was an early warning to public health officials and the produce industry that the international sourcing of produce means that infectious agents once thought of as only causing traveler’s diarrhea could now infect at home. The public health investigation of the 1996 outbreak couldn’t identify how, when, where, or why the berries became contaminated with Cyclospora cayetanensis. The investigation results were published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1997.1 I was asked to write an editorial to accompany the investigation report.2 In my editorial, I noted the unknowns surrounding the C. cayetanensis contamination. The 1997 spring harvest of Guatemalan raspberries was allowed to be imported into both the United States and Canada—and again, a large outbreak of cyclosporiasis occurred. As in the 1996 outbreak, no source for the contamination of berries was found. Later in 1997, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) prohibited the importation of future spring harvests of Guatemalan raspberries until a cause for the contamination could be demonstrated and corrective actions taken. While the FDA did not permit the 1998 importation of the raspberries into the United States, the berries continued to be available in Canada. Outbreaks linked to raspberries occurred in Ontario in May 1998.

When the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)-led investigative team published its 1997 outbreak findings in the Annals of Internal Medicine,3 I was again asked to write an accompanying editorial.4 As I had done in my previous editorial, I highlighted how little we know about the factors associated with the transmission Cyclospora on produce and how to prevent it. Unfortunately, the state of the art for preventing foodborne, produce-associated cyclosporiasis had changed little since the 1996 outbreak despite the relatively frequent occurrence of such outbreaks.

Thirty-two years after that first Guatemalan raspberry-associated outbreak — and a year after produce-associated cyclosporiasis outbreaks that were linked to U.S.-grown produce — we have taken a major step forward in our understanding of these outbreaks and how to prevent them. After Fresh Express produce was identified in one of the 2018 outbreaks, I was asked by the company leadership to bring together the best minds’ around all aspects of produce- associated cyclosporiasis. The goal was to establish a Blue-Ribbon Panel to summarize state- of-the-art advancements regarding this public health challenge and to identify immediate steps that the produce industry and regulators can take to prevent future outbreaks. The panel was also formed to determine what immediate steps can be taken for any future outbreaks to expedite the scientific investigation to prevent further cases and inform public health officials.

The Blue-Ribbon Panel comprises 11 individuals with expertise in the biology of Cyclospora; the epidemiology of cyclosporiasis, including outbreak investigation; laboratory methods for identifying C. cayetanensis in human and food samples and the environment; and produce production. In addition,16 expert consultants from academia, federal and state public health agencies (including expert observers from the FDA, CDC, U.S. Department of Agriculture, and California Department of Public Health), and industry, including producers and professional trade association science experts. The collaboration and comprehensiveness of this effort was remarkable. Many hundreds of hours of meetings and conference calls took place to determine our findings and establish our recommendations.

This document, “Interim Report: Blue-Ribbon Panel on the Prevention of Cyclospora Outbreaks in the Food Supply,” summarizes the state-of-the art practices for the prevention of C. cayetanensis contamination of produce and priorities for research that will inform us as we strive to further reduce infection risk. Also, we make recommendations on how to more quickly identify and more effectively respond to produce-associated outbreaks when they occur. We greatly appreciate all the organizations represented on the panel and the expert consultants. The report does not, however, represent the official policy or recommendations of any other private, academic, trade association or federal or state government agency. Fresh Express has committed to continuing the Blue-Ribbon Panel process for as long as it can provide critical and actionable information to prevent and control Cyclospora outbreaks in the food supply.

Thank you to all the individuals who contributed to this important effort. This unique partnership of individuals, organizations, and firms represents the best in collaborative and consequential public health action.

Sincerely,

Michael T. Osterholm, PhD, MPH

Regents Professor

McKnight Endowed Presidential Chair in Public Health Director, Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy Distinguished University Teaching Professor, Environmental Health Sciences, School of Public Health

Professor, Technological Leadership Institute College of Science and Engineering Adjunct Professor, Medical School

University of Minnesota

and

Chair, Blue-Ribbon Panel on the Prevention of Foodborne Cyclospora Outbreaks

And, why this report was written:

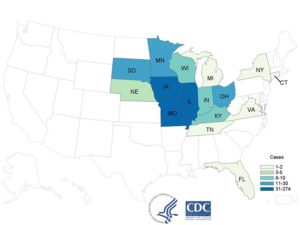

In 2018 the CDC, public health and regulatory officials in multiple states, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) investigated a multistate outbreak of Cyclospora cayetanensis infections.

As of September 11, 2018, CDC was notified of 511 laboratory-confirmed cases of Cyclospora infections in people from 15 states and New York City who reported consuming a variety of salads from McDonald’s restaurants in the Midwest.

As of September 11, 2018, CDC was notified of 511 laboratory-confirmed cases of Cyclospora infections in people from 15 states and New York City who reported consuming a variety of salads from McDonald’s restaurants in the Midwest.

Twenty-four (24) people were hospitalized. No deaths were reported.

Epidemiologic and traceback evidence indicated that salads purchased from McDonald’s restaurants were one likely source of this outbreak.

On July 13, 2018, McDonald’s voluntarily stopped selling salads at over 3,000 locations in 14 states. The company has since reportedExternal that it has replaced the supplier of salad mix in those states.

On July 26, 2018, the FDA completed final analysis of an unused package of romaine lettuce and carrot mix distributed to McDonald’s by the Fresh Express processor in Streamwood, IL. The analysis confirmed the presence of Cyclospora in that sample.

What is Cyclospora?

What is Cyclospora?

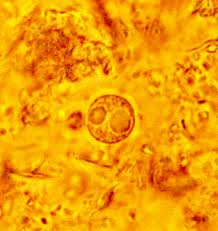

Cyclospora is a parasite composed of one cell, too small to be seen without a microscope. The organism was previously thought to be a blue-green alga or a large form of cryptosporidium. Cyclospora cayetanensis is the only species of this organism found in humans. The first known human cases of illness caused by cyclospora infection (that is, cyclosporiasis) were first discovered in 1977. An increase in the number of cases being reported began in the mid-1980s, in part due to the availability of better diagnostic techniques. Over 15,000 cases are estimated to occur in the United States each year. The first recorded cyclospora outbreak in North America occurred in 1990 and was linked to contaminated water. Since then, several cyclosporiasis outbreaks have been reported in the U.S. and Canada, many associated with eating fresh fruits or vegetables. In some developing countries, cyclosporiasis is common among the population and travelers to those areas have become infected as well.

Where does Cyclospora come from?

Cyclospora is spread when people ingest water or food contaminated with infected stool. For example, exposure to contaminated water among farm workers may have been the original source of the parasite in raspberry-associated outbreaks in North America. Cyclospora needs time (one to several weeks) after being passed in a bowel movement to become infectious. Therefore, it is unlikely that cyclospora is passed directly from one person to another. It is not known whether or not animals can be infected and pass infection to people.

What are the typical symptoms of Cyclospora infection?

Cyclospora infects the small intestine (bowel) and usually causes watery diarrhea, bloating, increased gas, stomach cramps, loss of appetite, nausea, low-grade fever, and fatigue. In some cases, vomiting, explosive diarrhea, muscle aches, and substantial weight loss can occur. Some people who are infected with cyclospora do not have any symptoms. Symptoms generally appear about a week after infection. If not treated, the illness may last from a few days up to six weeks. Symptoms may also recur one or more times. In addition, people who have previously been infected with cyclospora can become infected again.

What are the serious and long-term risks of Cyclospora infection?

Cyclospora has been associated with a variety of chronic complications such as Guillain-Barre syndrome, reactive arthritis or Reiter’s syndrome, biliary disease, and acalculous cholecystitis. Since cyclospora infections tend to respond to the appropriate treatment, complications are more likely to occur in individuals who are not treated or not treated promptly. Extraintestinal infection also appears to occur more commonly in individuals with a compromised immune system.

How is Cyclospora infection detected?

Your health care provider may ask you to submit stool specimen for analysis. Because testing for cyclospora infection can be difficult, you may be asked to submit several stool specimens over several days. Identification of this parasite in stool requires special laboratory tests that are not routinely done. Therefore, your health care provider should specifically request testing for cyclospora if it is suspected. Your health care provider might have your stool checked for other organisms that can cause similar symptoms.

How is Cyclospora infection treated?

The recommended treatment for infection with cyclospora is a combination of two antibiotics, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, also known as Bactrim, Septra, or Cotrim. People who have diarrhea should rest and drink plenty of fluids. No alternative drugs have been identified yet for people with cyclospora infection who are unable to take sulfa drugs. Some experimental studies, however, have suggested that ciprofloxacin or nitazoxanide may be effective, although to a lesser degree than trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. See your health care provider to discuss alternative treatment options.

How can Cyclospora infection be prevented?

Avoiding water or food that may be contaminated is advisable when traveling. Drinking bottled or boiled water and avoiding fresh ready-to-eat produce should help to reduce the risk of infection in regions with high rates of infection. Improving sanitary conditions in developing regions with poor environmental and economic conditions is likely to help to reduce exposure. Washing fresh fruits and vegetables at home may help to remove some of the organisms, but cyclospora may remain on produce even after washing.

Some background from thee CDC:

- Domestically Acquired Cases of Cyclosporiasis — United States, 2019

- Domestically Acquired Cases of Cyclosporiasis — United States, May–August 2018

- Cyclosporiasis Linked to Fresh Express Salad Mix Sold at McDonald’s Restaurants — United States, 2018

- Cyclosporiasis Outbreak Linked to Del Monte Vegetable Trays — United States, 2018

- Cyclosporiasis Outbreak Investigations — United States, 2017

- 2016 Update

- Cyclosporiasis Outbreak Investigations — United States, 2015

- Cyclosporiasis Outbreak Investigations — United States, 2014

- Cyclosporiasis Outbreak Investigations — United States, 2013

Marler Clark, The Food Safety Law Firm, is the nation’s leading law firm representing victims of Cyclospora outbreaks. The Cyclospora Attorneys and Lawyers have represented victims of Cyclospora and other foodborne illness outbreaks and have recovered over $650 million for clients. Marler Clark is the only law firm in the nation with a practice focused exclusively on foodborne illness litigation.

If you or a family member became ill with a Cyclospora infection after consuming food and you are interested in pursuing a legal claim, contact the Marler Clark Hepatitis A attorneys for a free case evaluation.